The Story ⚡

A Yoruba-inspired sci-fi animation backed by Disney and created by Shofela Coker – Moremi will debut globally on July 5th 2023.

The plot details follow a Lonely spirit boy Luo who is trapped in the realm of the gods and haunted by terrifying giants until he is suddenly rescued by Moremi, a daring scientist from future Nigeria. With the giants in hot pursuit, they escape across the country and head for the sanctuary of Moremi’s lab.

As Moremi helps Luo connect with his lost memories she reveals the truth of the terrible sacrifice that was once made to save their people.”

“Moremi” features as the fifth episode of the Disney+ series Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire, and was co-written by Vanessa Kanu.

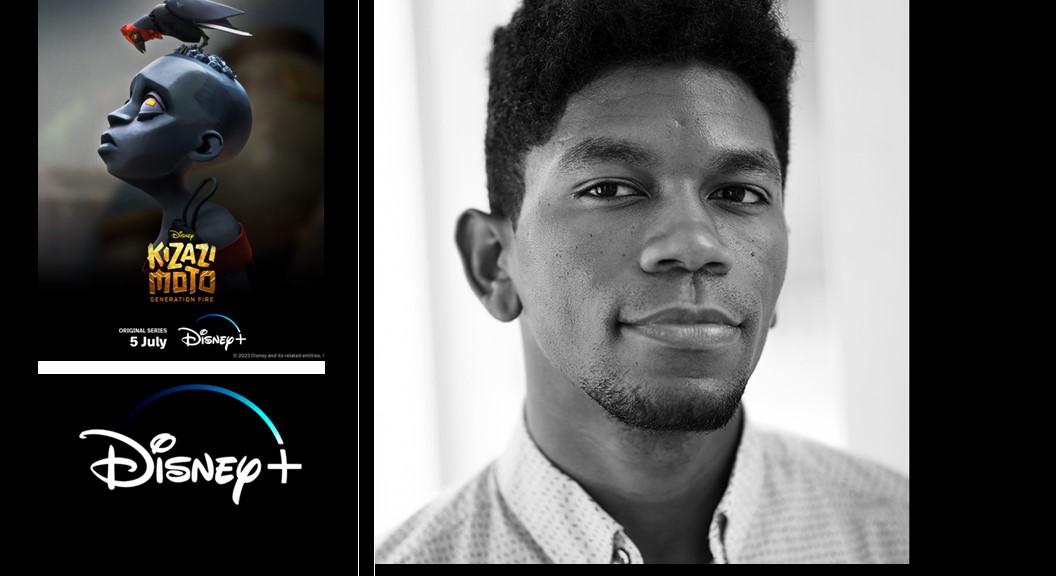

In this exclusive, Shofela Coker walks us through his journey of creating the Moremi episode, from conception, casting, visual references and what this project has taught him as a filmmaker.

Let’s talk about your journey from pitching the right story to getting picked

it was quite a ride. I mean, Triggerfish was a studio that reached out to me initially, and they had seen my work previously on a film called Liyana. And some of the work I had done in comics and art direction over the years. So when I heard the brief, for me at the time, I was really longing for home in the sense that I lived in the US for quite a while and I wanted to go back to Nigeria to visit, in particular.

So I pitched to Disney and Triggerfish an idea to explore a story that dealt with those themes. And for me, I grew up with a story. I read it in the book when I was a kid. I think everyone in Nigeria has either had some contact with it or the other, like through a song or a play, through mythology.

And I love mythology in particular. So the story of Moremi presented a framework that I could explore these themes and tackle them in a new way through science-fiction and bring maybe, hopefully, maybe not something new, but say something more about the conversation because I feel like that’s what you do with mythology.

If you write a story with that framework, you’re using a primordial basis to explore identity. The pitch process for us was pretty clear. They reached out to about 300 creatives in Africa, and I pitched this idea to them and they whittled it down to 80 people. And then over a few months, they whittled it down to 33 or about 30-something people. And then there were 15, and then there were 10.

So it was quite a journey through these stages before production started.

Did you experience any creative limits while working to create?

There are always creative limits, and I think that gives rise to clearer creativity if you’re playing in a set sandbox it’s better for me, anyway. So the brief was science fiction, optimistic stories about Africa, and there was so much freedom from there. I think that’s what we were mostly lucky with on this project.

And I think it’s unprecedented how much support they gave to us in terms of creative support and financial support as a Disney platform.

So the ethos of the project is to give a platform to authentic voices on the continent. And they supported that in every way in the process, from the feedback to setting us up with studios that could allow us to do that.

I think a lot of people are wary of the idea that Disney comes in and tries to tell African stories. But the ethos of the project is just that. It is giving, whether it’s a Nigerian voice or Egyptian voice, an actual platform to be as free as they can of storytelling. And it was supported, too, throughout the whole project.

We had master classes and mentorship. Peter Ramsey was one of our mentors and Sidney Kombo from Weta Digital was another one of our amazing animation mentors. So there was very clear support in that sense.

The casting process, how did you go about that?

So Tolu Olaoye was the cast voice for the boy – Luo. I’ll talk about him, first of all, because it took a long time to find him. I think during the casting process, they found great talent in a lot of young women or women. We hadn’t found the voice for the young male character.

And when we finally found Tolu’s voice, there was a fragility and kind of a little bit of a roughness to his voice that I loved. He sounded like all the Nigerian kids that I grew up with there’s a little bit of mischief in there, but there’s a vulnerability that I heard in his voice that I loved.

All the casting was done blind.

I only listened to a number of actresses as they all had a set number of lines they had to read.

There’s a song in the film that the actresses were required to sing for the audition. And as I said, I didn’t know it was Kehinde Bankole, but when I heard her sing, there was something about the quality of her voice that was almost ethereal. She has a gravity, a natural gravity that I think a lot of people gravitate towards.

And the character called for a kind of regal sensibility. She’s a brave woman, but there is a little bit of vulnerability in Kehinde’s performance that I was so drawn to. And I think that’s why I loved working with her.

She brings something special in terms of the gravity of her performance, but there are also layers to it. And specifically, it was that quality of her voice that was a little bit fragile, a little bit smoky, and not perfect.

And I think the imperfection of her voice is actually what makes her singing voice and her speaking voice so beautiful. Yeah, it was a joy to work with her.

Kehinde has a history with the character Moremi. She’s played Moremi on the stage for theatre, but I didn’t know that up until we worked together.

How do you create a story mixing Afro-futurism and mythology while also telling the future with a story from the past?

I have an art direction background. So for me, with storytelling, the visuals have to match the story one to one.

They have to be in step. The story is key, but the visuals have to support it in every way possible.

And in our film, I think my general style is I like to include patterns in the work, in the background specifically.

Our film was about looking at the past, considering present identity and projecting a future of Nigeria. So we looked at references from Nigerian artists I love like Lamidi Fakeye, and Nike Davies- Okundaye, the textile designer.

We pulled from inspiration that was specifically contemporary Nigerian artists, like Lagos Space Programme, but mostly Nigerian artists from the 60s and 70s. And of course the historical stuff.

There are two worlds in our film, there’s the world of the spirits and there’s the world of living. And we pulled a lot of references from ancient Ife and ancient Benin to create a juxtaposition of these worlds.

I worked with a production designer called Yinfaowei Harrison, lockstep to design the world initially when we pitched it. So it did have a bespoke Nigerian look and philosophy to it.

We looked at architects like Demas Nwoko and architecture from the University of Ife, to contemporary designs in Lagos. There are a lot of touch points in Nigerian cultural history that infuse the story with a striving for, an ideal for what I’d like to see us move toward in the future and adapting the Moremi myth itself is a beautiful way I feel to do just that.

What’s the one thing that you got out of the executive mentorship that helped you push through to finally deliver your episode?

Challenging question. I think specifically Sydney’s sessions were very technical and focused in terms of how to achieve the best look for animation for what we were trying to do with the story.

So there was that kind of support, but I think from Peter and Tendayi Nyeke, Anthony Silverstone, and the executives that worked on developing the story imparted a strong crash course in methods to refine the story so that the North Star, the theme, the idea that we were trying to get across in the story is always in the foreground. So that’s something I will take forward with me.

I think as a young Director or filmmaker you always want to try and put as much into the story as you can because all these ideas, you finally have your chance you want to put all these ideas into the story.

But I think they showed me methods and advice to hone a story and make sure that you do get that true kernel of truth in your story. So that’s something I will take forward with me.

What’s the fun thing that you included in your episode that you think everybody’s gonna go crazy when they see it?

Okay, there are a few. There’s a line that came with working with Vanessa Cannon, who’s the co-writer with me on this project. She talks about Jollof Rice, so there’s a reference to Jollof Rice in there.

There is a moment when one of the characters, the young boy in the film does a traditional Yoruba bow, when you’re greeting your elders, you have to show deference by prostrating.

There’s a moment in the film where the boy does that. And I fought very hard to retain it because it’s a short film, and there’s not much time to tell the story. And you have to be very efficient with what you choose to say with your characters and do.

So that was very important for me to get that little bit of mannerisms, behaviour, and specificity of Yoruba culture. So that was a fun thing.

In terms of music choices, what was your approach to scoring the film? And was there any need for you to connect with other episodes that were in the anthology

No, I think you’ll see that when you watch a lot of the shorts there are connected threads but they’re all standalone episodes. We all had our own stories and directives about how we achieve those stories and specifically with music.

We all worked with one music supervisor who turned out to be one of the composers of Moremi- James Frank Bassigthwaighte, who’s a composer, with Femi Koya, a multi-talented musician/ singer and Olaolu Lawal, who was also a composer and a musicologist on the film.

Essentially they were all working together to craft this score with me with the idea that they would blend traditional Yoruba instrumentation with electronica.

Olaolu was crucial for the film in terms of developing the sheet music for some of the folk songs that you hear in the film as well. One of my favourite parts of working on the film was developing this language. Because it was something new. It was blending the Batta, the talking drum, with an electronic landscape as well. And trying to craft a future sensibility with Nigerian music, with Yoruba music in particular.

So yeah, I’m mostly an art director and visual director, but I found, this is something that I want to put in the fore of a lot of my projects. And you’ll see when you watch the film that the music and sound design are very important to the story.

They were amazing for helping to lift and elevate the story in that way.

Were you initially co-writing on this project?

So I came up with the idea and the outline, but I requested to work with a Nigerian writer because I’m very interested in collaborating with people to elevate the idea of a story like this.

I read a few people that Triggerfish provided as potential people to work with, and Vanessa Kanu’s work stood out to me. She has a very specific sense of humor and also her sensibility about storytelling in terms of the supernatural was very interesting to me. This was like a few months into the process of script writing.

Vanessa came on board and she contributed so much to the film in terms of humour and her sensibility. Something I love doing is making sure I work with people that are passionate about what they do and are in service to an idea. Because I feel like that’s the best way to make creative work like this.

Lead less with ego and more with being in service to an idea- a mantra my producer Ingrid de Beer and I tried to lead with. And I think if you see the film, you’ll maybe understand where I’m coming from with that. Because it is all about giving to the story of Moremi, contributing to that legacy, and less about one person’s idea or vision.

It took a village to make this film!

What do you think this project with Disney means for you?

For me, the most important thing was being connected to African creatives in particular. The project was designed around trying to lift African creatives that I had known for a long time.

Putting them in positions where they could either be in a leadership role or contribute some kind of major element to the film. And I think that’s the ethos of this that I believe in, is making sure that there is a pathway for people like you and me to say something on the global stage.

It’s not just about Disney providing that. If this works, I think other sources of funding, whether it’s from other streamers or even within the continent will provide more infrastructure, more funding, and more sustainability to this industry.

I believe in the African animation industry and I want to see it thrive. I want to work more in this space. So that’s the hope for me.

Kizazi Moto Generation Fire debuts only on Disney from July 5th 2023.