The Story ⚡

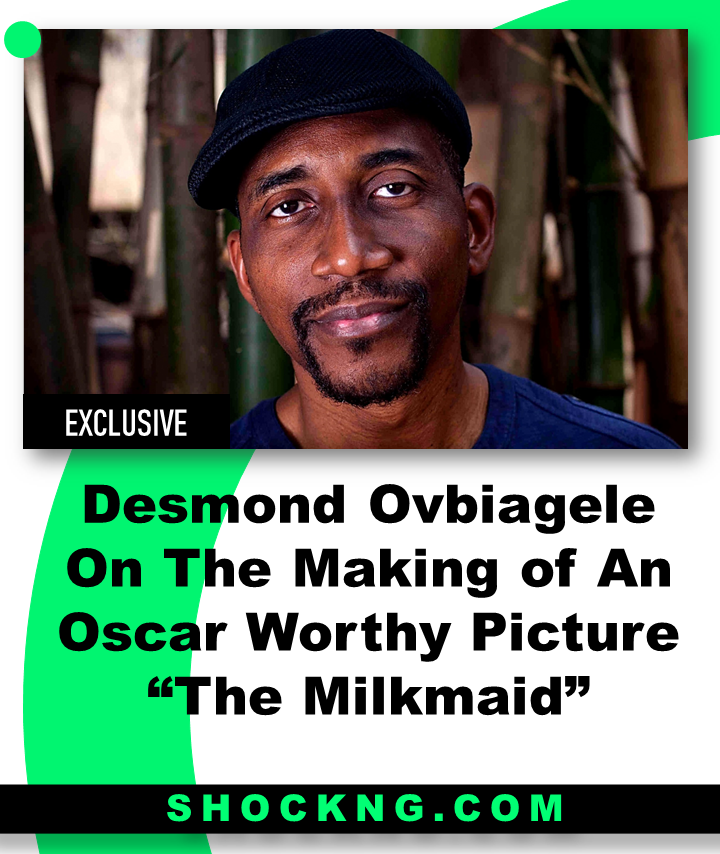

The Milkmaid directed by Desmond Ovbiagele is now accessible for domestic audiences to watch.

In 2020, the title became the first Nigerian title to scale through the Oscars’ rules and eligibility and was submitted as Nigeria’s entry to the international feature category.

This interview with the writer/director provides a rare window into the making of this Oscar-worthy picture shot on location in Taraba, Nigeria for three months, its spending investment range and why it is just finding a home for audiences to watch.

Let’s Begin.

When did you shoot the film and what gave the green light to go ahead?

We shot The Milkmaid about three/ four years ago. Obviously, COVID disruptions created an indent to the plan. But essentially, we all moved down to Taraba once the script was written and talents (both in front of and behind the camera) were ready.

There was also the green light from the Taraba State government. We had consulted with and written to the state government, requesting their partnership on the film, with the hope that it not only served the interest of our film in terms of availability of locations but also help promote a very picturesque state which had not received that sort of attention either locally or internationally. So we hoped that it would be a win-win situation for both sides. And the government saw it that way as well

When they signed off on that and were onboard to facilitate the production, the last step was raising funds.

Thinking about the entirety of the partnership, do you think it has been done before or were you the first for the state?

Well, in terms of filmmaking in other states, certainly it has been done, but I believe it was the first for Taraba state.

“Milkmaid” did something right as regards production value. How were you able to get that part right for the film?

First of all, thank you very much. Secondly, I can’t discount a divine element being involved. I can’t take full credit for that. Neither would any of my cast or crew want to do so.

But what you aim to do is to have as lofty and as noble a vision as you can; a genuine and legitimate intent to portray the story to its fullest extent such that it can travel anywhere internationally in terms of production values, technical quality, creative quality, and then you go for it.

And then the outcome is really not under your control. You can only have a vision and then step out, do your best to actualize it, and then the outcome is, to some extent, beyond you.

So that’s what we did. In terms of things like the acting resources, we conducted a couple of auditions in Taraba state, and we were pleasantly surprised to see the depth of talent in a location as undiscovered as the terrain in Taraba.

There have been comments about “Milkmaid” being a Nigerian film that doesn’t feel like a Nollywood movie. Thoughts on this comment?

Obviously, Nollywood has a breadth of artistic and creative expression. So even Nollywood, as it was in the early 90s, is itself changing. And I’m sure you find out right now that Nollywood does encompass a much wider variety of styles than it used to. Perhaps this particular style is not prevalent, so to speak, but we just tried to incorporate a location that hadn’t been accessed before cinematically, so certainly that would have helped in terms of the look.

For the cameras, we definitely wanted to use the highest grade cameras possible to render images in what we consider to be a spectacular location. So we deliberately went for cameras which we knew had been used on Oscar-worthy films in Hollywood. That wasn’t cheap, but we thought that the nature of the story and location deserved that sort of technical treatment.

There’s a style to these sorts of movies which not many people are interested in, but we were certainly interested in it in terms of the way it’s edited, in terms of the composition of the frames, camera angles, light and things like that. For me, it was important for us to get a cinematographer who totally dialed into that sort of style and knew exactly what to do. And that’s how valuable Yinka Edward was to the production resource.

Can you take us through the emotions or reactions you were trying to evoke while writing this script?

Yeah, well, it was a product of research. I needed to do as much research as possible to ensure that when I’m writing characters, they are authentic and legitimate to the story we’re trying to tell.

So I read and watched several survivor testimonies of their encounters with the extremists.

I actually had an opportunity to have a couple of interviews with victims of the insurgency who I encountered in Lagos. I wasn’t even aware that there was a small settlement of escapees who had made their way all the way from Borno to Lagos to try and pick up the pieces of their lives.

I got in touch with an NGO that facilitated my access to these women. One of the things that struck me was that had I not spoken to the women, I’d have never had an idea that these people had undergone such harrowing encounters and circumstances. The word that describes their attitude was resilience. You know, these people have been through extreme trauma, had lost loved ones but yet were still soldiering on the best way they knew how.

They were staying in the settlement rented to them by area boys who were extorting money from them. What money did they have? But somehow with little to no assistance from anybody, they were managing and somehow trying to eke out an existence.

What I discovered was that the number of these women and children that you see sometimes on the streets of Lagos are actually from that territory.

You see them begging in traffic with their babies and you don’t really know where they come from. You think they’re being lazy or whatever it is, but that is how some of these people try to sustain themselves.

There seems to be a continuous spread of insecurity and insurgency in the country. Can i get your thoughts on the government’s efforts? What do you think is really going on?

Well, in terms of the outcome of the government’s efforts, I think there’s no need to comment about that, we see it.

In terms of why the situation persists, clearly, efforts have been made but much more needs to be done. The situation is clearly deteriorating to some extent, and I think it’s a problem that needs to be engaged by multiple stakeholders with genuine intent. I think that it’s an issue that many people would like to shy away from, would like to sweep under the carpet and to some extent would like to be like the proverbial ostrich, ‘hide your head in the sand and if you can’t see the problem, then it doesn’t exist, but that’s not how it works. Turning to other distractions, entertainment or otherwise, or business or whatever it is that can take your mind off it, doesn’t change or in any way affect the problem. It will just continue to grow.

So unless we tackle it wholeheartedly and not just the government, everybody who has something to contribute should focus on it and contribute their bit. I think that’s the only way it can be resolved. If we say it’s a government or military issue, and we think we can get on with our lives, we are deceiving ourselves.

Everybody has a part to play, unless we are willing to, from our own little corners, contribute our bit to see that it’s resolved, then it will continue.

Because that’s just the immense nature of the problem. It requires all hands on deck, not just a segment of society.

From a cultural and landscape view, how were you able to make that vision come alive?

Yeah, because of the nature of the story, particularly right now on the back of the Chibok Girls’ abduction and all the global outrage, we knew that if we’re making a global film, it would have access to an international audience because they’re interested in trying to understand the phenomenon. Once we established that there would be that potential access to international audiences, we also wanted to take advantage of the opportunity to showcase both the good and the bad.

Not just talking about people who are killing and oppressing, but also to understand their culture, their customs, their language, how they interact with each other, and what their hopes and dreams are. So it’s an opportunity for us to showcase the richness of the culture in that region.

Once we had that vision, it became a question of looking for the resources, human and material, to realize that.

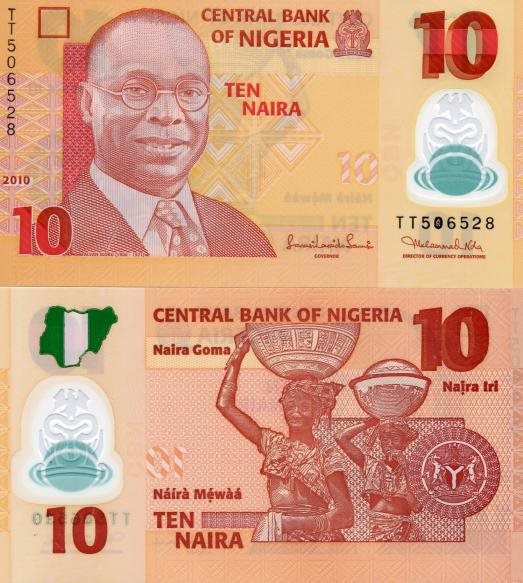

On the title of the film, why did you go with the title “Milkmaid”?

Well, the story itself was inspired by the two Fulani milk maids at the back of the Nigerian notes. And the whole idea, the story sort of started out with taking those two young ladies carrying calabashes on their head, fura da nono, as a starting point and coming up with the creative imagining of what will happen with these two young girls.

And that picture was taken in a relatively serene time of the late 60s or early 70s. But just imagine these two young girls who were leading this very peaceful existence, where they own and operate their business in a conflict-ridden zone, being directly impacted by insurgency and how their lives turned out. So that really was the inspiration for both the narrative, the characters, as well as the title of the film.

You represented Nigeria at the Oscars for the international feature category. Did that have an impact on the visibility of the film on an international scale?

No doubt, for you to not just be selected to represent your country at the Oscars, but to be the first-ever successful submission, certainly that attracted attention.

Everyone knew about Nollywood for several years now, but this was the first submission by Nigeria that was accepted by the Academy. Of course, people were curious to find out what sort of film this is. They are familiar to some extent with the style and content of Nollywood films in the past.

They were curious as to what was going to be different, and why Nigeria selected this particular film to represent it as a first submission. So, yeah, there was certainly that natural curiosity which certainly opened doors for various screenings internationally.

Moving to the Nigeria Video Censors Board, trying to get the film on big screens, can you take us through the challenges you faced?

Well, the film went through the normal process any film goes through in Nigeria with the Censors Board to enable it to screen cinemas in the country. Like the Censors Board normally does, if it has any issues with any film, it will provide its comments so they can be addressed, to enable it to issue the requested classification. “Milkmaid” went through that process, we submitted it, they watched it and had their comments.

We went back and forth a bit in terms of just trying to arrive at a solution that enabled them to proceed with their classification, but eventually, we arrived at a solution.

And we did screen the film in cinemas albeit, for a very limited period, I think just a couple of weeks to enable us to qualify for Oscar consideration.

Were there plans on doing that before or was it a strategic move to qualify?

Well, a cinema run was obviously always was an option for us, but our immediate objective at that point in time was to facilitate the film’s eligibility for consideration.

The idea was to do a limited release and explore a wider one sometime after that.

With a story as unique as “Milkmaid”, what were your plans as regards distribution?

Well, we wanted to exploit all the available windows. From the big screen, and then moving on from there to subscription platforms like Netflix, Amazon and the likes, as well as places like airlines. Whatever window, really, all available distribution windows were on the table for consideration. It was just a question of negotiating and then finding out which ones were the best ones to go to and in what order.

Seeing as Nollywood is getting huge international attention, what do you think are the stories we should be telling?

Great question. Nigeria is a very diverse society with diverse languages, people, customs and various aspects of society. And obviously, there’s a lot that’s going on.

What I’d like is to see us as filmmakers, as an industry, be as forthright, as creative, as brave and as adventurous as possible, which is what is required for the development of any industry. So every form of content, every form of narrative has a legitimate place at the table, we just need to ensure that we have a very robust industry that is very expressive and representative of all aspects of our society.

Although there’s a perception in Nollywood films about the films that do well or should do well, they are typically “feel good” films that make you laugh, but as an industry, we have to look at other industries like Hollywood and see that they present a broad variety of content addressed in various facets of the society.

I will certainly like us to take a cue from them.

Making this project in Hausa made the production elongated as you don’t speak that language and had to use a translator all through. Would you take that decision back if you went through the process again?

We were striving for as much authenticity as possible in terms of the characters and the story, and it simply didn’t connect with us, that you’re making a film about insurgency, and they’re speaking Queen’s English. It just didn’t translate.

And apart from that, I said we wanted to explore the opportunity to showcase the culture and part of that was the Hausa language itself. In addition to that, if we hadn’t shot it in an indigenous language, we would not have been eligible for consideration for the Oscars. So, definitely no regrets on that front.

Can you kindly share the investment range needed to make this project?

We knew that a film of this nature, of this sort, would certainly be pushing northwards of a quarter of a million dollars at least and possibly much more; considering the cameras and lenses we used in shooting the film.

Also considering where we shot the film, which is at the extreme eastern tip of the country, sharing a boundary with Cameroon, we were mobilizing resources from the other side of the country southwest. Logistically it was going to take quite a bit financially to actualize.

Some things we didn’t plan for budget-wise, like the length of time caused by translation necessities to actually shoot the film. So those added on to what we had already expected to be a reasonably high budget.

How many sets did your team have to construct for the shooting of the film?

I would love to give you a precise number, but I can’t. All I can say is we constructed several sets. We had the benefit of the profound skill and experience of Pat Nebo who is probably the foremost production designer in Nigeria. And as his custom, he looked for several ways to save the production money by being as creative as possible with sets and being able to use one location for different things by converting them this way and that. So that definitely bailed us out of several jams.

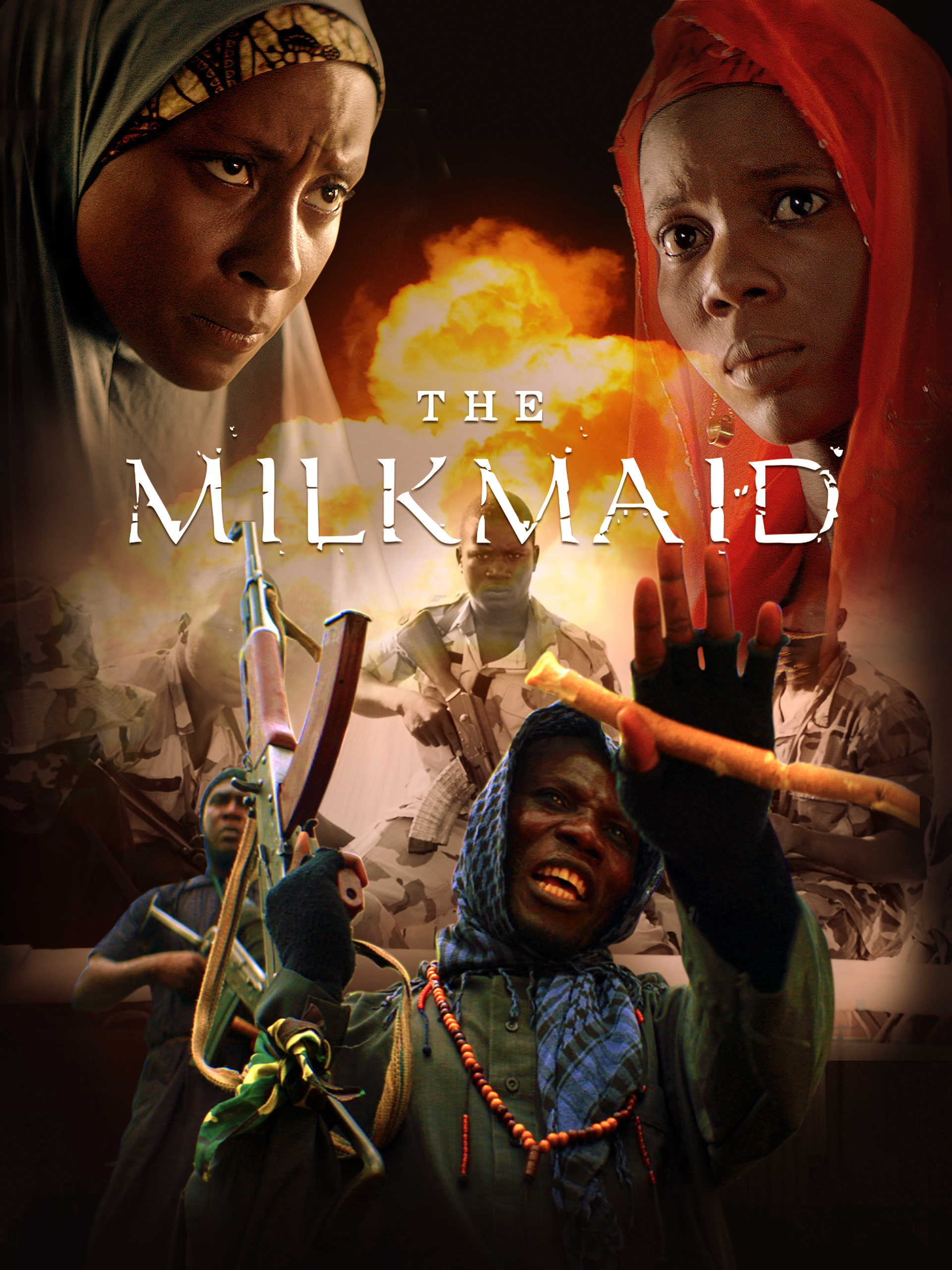

Now that it’s on a streaming platform, what is that one thing you want the audience to take note of while watching “Milkmaid”?

We are trying to shine a light as regards the experiences of those most impacted by the insurgency situation, and not just in Nigeria. Unfortunately, it’s a growing phenomenon in neighbouring countries and even in places like Mozambique, Burkina Faso and Mali.

But what we’re trying to present is some insight into the lives of the people involved in the crisis, both on the sides of the victims as well as perpetrators, trying to understand what the motivations are:

Who are these people? What do they want, how do they live and how do they cope with what they are going through or what they are inflicting on other people? How do they respond to that as human beings? Because that’s what they are at the end of the day, they are not monsters or demons but humans, some of whom are grossly deceived in terms of how they should go about expressing whatever grievances they have, and show that they have hopes and aims.

I hope that Milkmaid at the very least presents an angle of insight into that situation for the audience to see.

Can you walk us through your post-production?

They say you make a film three times, or you make three kinds of films. There’s a film that you write in the script, there’s a film that you actually shoot on set which is different from what the script is, based on the exigencies of the situation.

And finally, there’s a film that you actually put together in the post-production studio, which, again, is quite frequently different from what you actually shoot. So these are three different visions, which you hope to get as close as possible to the original vision you set out to do.

So having been through the scripts, shooting, and then coming into post-production, the goal was to try to preserve what made us all excited about the story in the first place, to protect that in realizing the final output. Then once you have that as an objective, you want to use the best possible hands to actualize that, to make sure your editor is in sync with you mentally and also has the technical capability to put together the film to adhere to the original vision.

It takes time because when you get into the rushes of the film, you discover many things that were not done in the way that you originally intended to, and then you have to make a decision as to whether to change that aspect of your vision or whether to redo it to ensure that vision retains its place. So, again, post-production is all about decision-making, being confronted with the reality of what you’ve done and deciding on how to shape that reality.

During the course of the film, did you have to reshoot any particular scenes?

We didn’t really have a strong need for reshoots with what we had, thank God. Things like ADR, where the actors have to render unclear dialogues again are a regular part of post-production, and we definitely did that, but we were quite fortunate that we didn’t have to do any reshoots that were necessary to save the film or to actualize the vision.

Moving to Sound Design

Sound design is an integral part of any film, some say the sound design is even more important than the visual look of the film. If you have a bad sound in the film, the audience will not overlook it. So it was very important for us to capture high-quality sound as much as possible, not just capturing the sound of the dialogue, but also capturing the ambience of Taraba state itself, which was very rich.

We wanted to use those sounds creatively to add impetus to the narrative of the story and to add texture. We went the extra mile to capture the ambience of an environment in the northeastern part of Nigeria, to add that to the sound fabric, the aural fabric of the film. In addition to that, the soundtrack, and the musical composition were important for that to be in sync with the characters and the setting of the story. You couldn’t just have Hollywood musical themes going on in the film. We wanted to localize that as much as possible.

We had a very experienced and creative gentleman called Michael Ogunlade, aka Truth, who rendered very creative compositions on the soundtrack which we’re very appreciative of. It was also a bit of a boost to us that he himself had actually spent his formative years in the north. He was attuned to some of the rhythms and musical influences of the area which he sought to put and use as a stepping-off point to create the soundtrack for the film.

Can you take us through your background? Past projects and the likes.

The “Milkmaid” is my second feature, my first was a film called “Render to Caesar”, which was released in 2014, it went through the cinemas and a number of festivals abroad.

The title was a crime drama and unlike “The Milkmaid” it was not an indigenous language film, it was in English, shot in Lagos and featured a number of very notable Nollywood actors and actresses. That was my first step into the film industry and it was an educational experience.

Should be expecting anything from you very soon. Are you currently in development for a particular film story?

Yes, I am in development, very early stages, so not worth talking about right now because things may very well change. But yes, to say yes, I am certainly in active consideration and exploration of a number of projects, but hopefully, we’ll share a bit more about that in the months to come.

Thank you for this great conversation

Thank you

“The Milkmaid” is now streaming on Prime Video, Go See it.

This is a SHOCK Exclusive. Thank you for reading

Shockng.com Covers the Business of Film/TV and the Biggest Creators in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Let’s be Friends on Instagram @shockng

.